Articulation: How Notes Start

Wesley Campbell

Articulation, on trumpet as well as in speech, is how we start each sound, or each note. The largest contrast in articulation is the difference between slurring and tonguing. Simply put, slurring is moving from note to note without interrupting the sound, while tonguing separates the notes with, you guessed it, the tongue. Sounds simple, right? Well, in some ways it is, but there are many variations to tonguing. Let’s take a closer look.

Slurring

Slurring is, generally speaking, easier to do well. This is because when you do it right, the trumpet does most of the work for you. Remember when you changed notes just by pressing the valves back in Changing Notes? Chances are, you were probably slurring. When reading music, you’ll know when you should be slurring by the indication of the aptly named “slur mark,” which is just a curved line connecting the notes that you won’t be tonguing.

The most important thing to remember when slurring is that you shouldn’t let up on the air you’re blowing. If you do, the motion of the valves can interrupt the sound and your next notes may not come out in time, or sometimes, at all! This is particularly important when slurring upward. In that case you could be moving up to the next harmonic and lowering it by using the valves. Those actions happening at the same time require solid air support. Keep the air moving!

Tonguing

Tonguing is the flip side of the articulation coin, but that doesn’t mean everything becomes opposite. Air for instance, still needs to move. In a perfect world, you would want to keep your air moving the same when tonguing as when slurring. That said, tonguing accelerates the air slightly at the beginning of each note, so you can get away with a bit less air. For that reason, it can sometimes feel easier to move notes while tonguing.

Now, what is the tongue actually supposed to do? Well, say “Ta-da!” That’s basically it. Both the “ta” and “da” are common articulations used in trumpet playing. The particular vowel sound you use… well, that gets trickier. Sometimes you’ll want an “ah,” sometimes an “ee,” sometimes an “oo.” The different vowel shapes will affect the tone you produce through your trumpet, so play around with them until you determine which one makes the sound that you want. In general if we see notes written without a specific articulation, we should probably use “ta” or something close to it. The most common specific articulation markings you’ll see are staccato, accent, marcato, and tenuto.

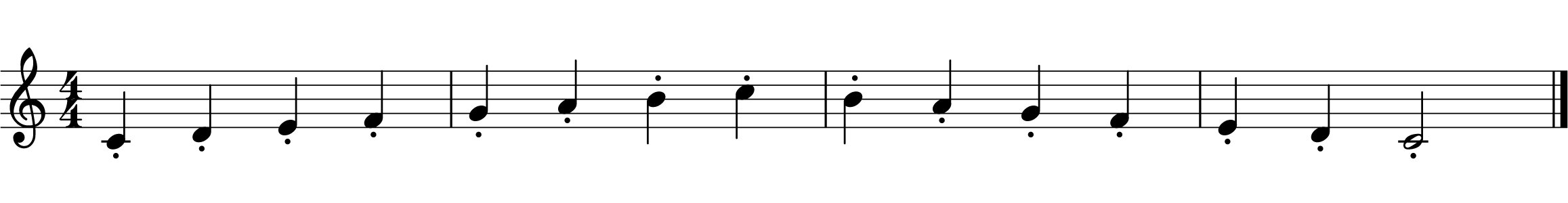

Staccato is the Italian word for “detached” and is indicated by a single dot above or below the note. This means the note should be separated from its surrounding notes, usually by shortening it slightly and making the front of the note a bit more pointed. To achieve this, simply tongue slightly harder and release the note (with your air) a little early. Think of how you might say “tut tut,” where the sound separates, and the second “t” in “tut” is more a stopping of air than an actual striking of the tongue (almost “tuh tuh”).

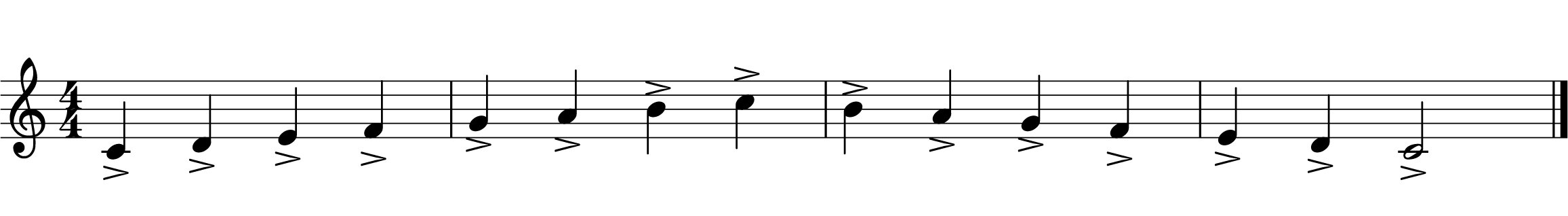

Accents are indicated with a symbol that is eerily similar to the “more than” symbol that you’ll find in math class. The good news in that association is that the accent symbol means the note needs more sound. Two ways to make the note stand out as louder are to either push more air or tongue harder. Incidentally, tonguing harder will in fact push more air. That’s why it’s the easier approach for most people. If tonguing harder is difficult, go for more volume through extra air for now. As this series progresses there will be more in-depth exercises for tonguing to help strengthen and refine articulation. But that’s getting ahead of myself.

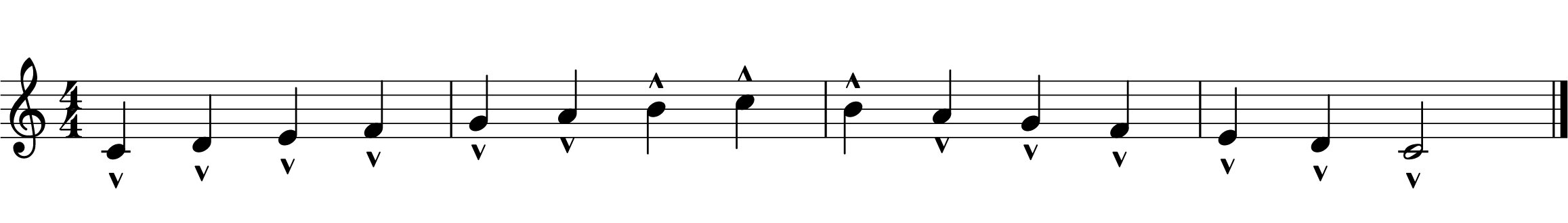

Marcato, Italian for “marked,” is essentially a louder version of an accent. These should be louder and more forceful. This generally means having an even harder striking of the tongue. Imagine trying to spit across the Grand Canyon and you’ll get an idea of how much force the tongue should be using here. Depending on the music style and your musical director, marcato may also indicate that the note should be shorter, like an accented staccato. This is particularly true in jazz. The mark for a marcato is much like an accent that has been turned on its side, with the pointy end facing away from the note.

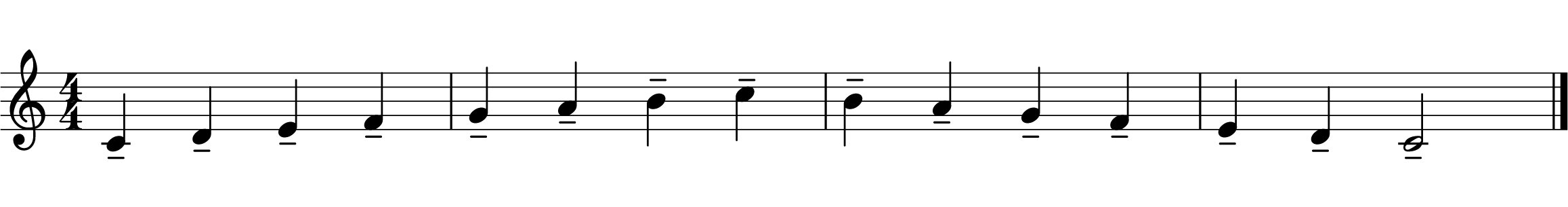

Tenuto, another Italian word, means “held” and is not technically an articulation, but an indicator of duration. A note with a tenuto marking, which is a simple horizontal line above or below the note, should be held for its entire value, connecting right up to the next note or rest. How we often achieve this on trumpet is by playing in a legato style. Legato is Italian (catching the pattern yet?) for tied together. In the most extreme, this would mean the notes have zero space between them. Slurring is the epitome of legato. That said, if a part is marked either with the word legato or tenuto markings on the notes and there is no slur marking, it should be assumed that you’ll need to tongue the notes very lightly. In this case, think of saying “da” rather than “ta.” Going to an even softer sound, you could try “na” or “la,” though those may take a lot of practice to use effectively.

These are not all of the articulations that we see in trumpet music, but they’re certainly the ones that we see first and most frequently. There are subtle variations that can be made on most articulations and even some markings that get stacked on top of each other! There are probably as many variations of articulations as there are sounds in speech. Practicing the different sounds will help put you in control of the trumpet so you can make it “say” anything you want.

Next time: a reader requested topic! Care and Maintenance of Your Trumpet