Changing Notes

Wesley Campbell

Now that you’ve played your first note(s) on trumpet, it’s time to play some more of them. By that I mean different notes. More of the same note is fine, too, but that’s working on endurance, and that’s a topic for a little bit later.

There are two main ways to change notes on the trumpet: changing valves and changing air. Note that I didn’t say lips. Yes, the lips will be involved. Yes, the lips will vibrate at a different frequency. BUT using the air to change the notes will allow you to play more notes sooner, and ultimately play more efficiently. We’ll get into that in a minute, so before I get too far ahead of myself, lets talk about the valves.

Using the valves on the trumpet is by far the easier way to change notes. As long as you’re playing an open note (that is, not pressing down any valves) you can instantly play more notes by pressing down valves. This way of changing notes lets the trumpet (and the nature of acoustics) do the work for you. So, how do the valves do that? Well, each valve (in the case of most trumpets, a piston) has precision machined holes in them to line up with specific tubing on the trumpet in two different positions: up and down. In the up position, airflow bypasses extra tubing and goes as directly as possible to the bell. In this manner, when all 3 valves are up (which we call an open note) the trumpet is at its shortest length. As the valves are pressed into the down position, airflow is diverted into the extra tubing attached to each respective valve. This lengthens the trumpet overall, making the sound automatically move lower in pitch (thanks resonance!).

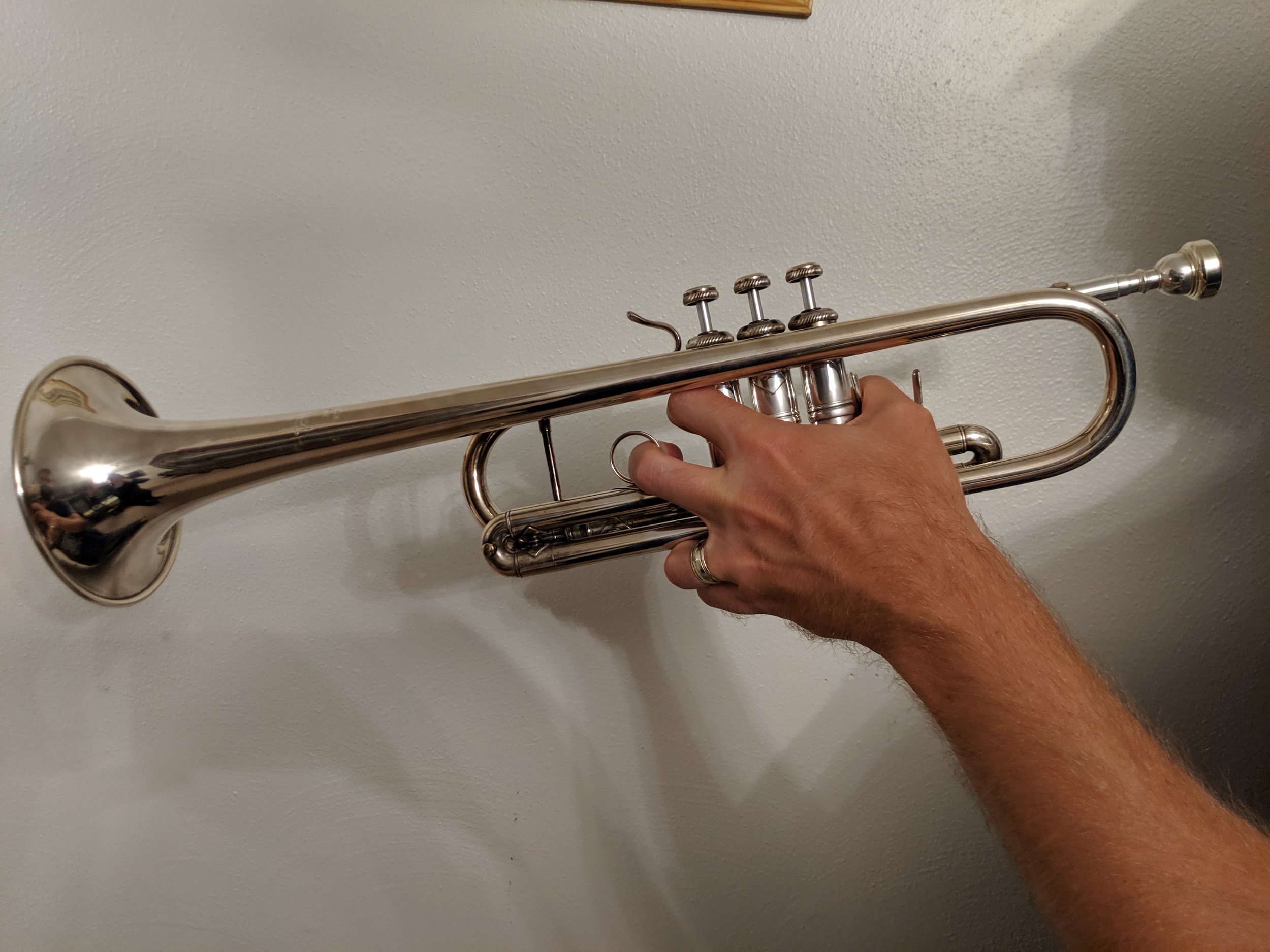

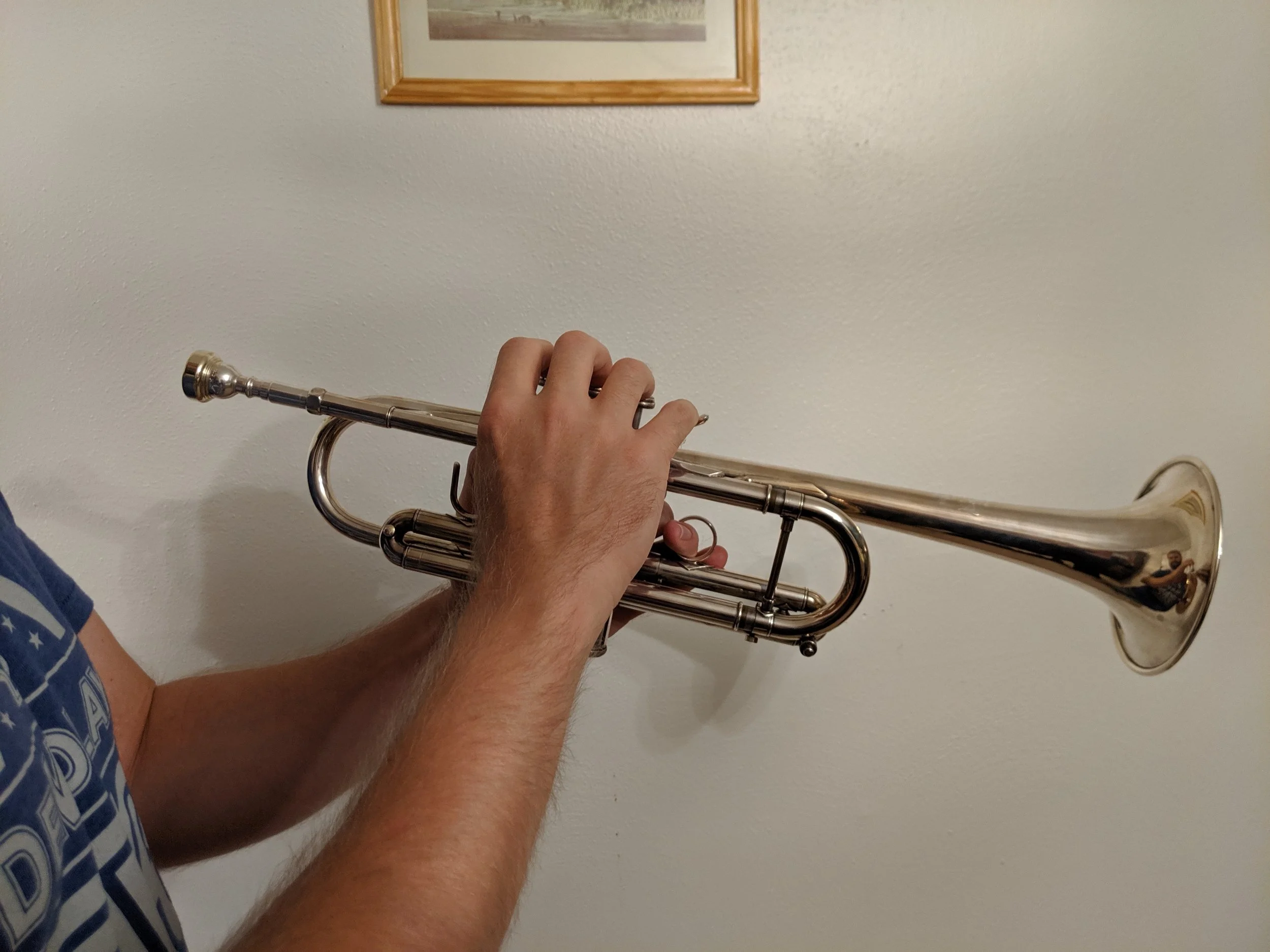

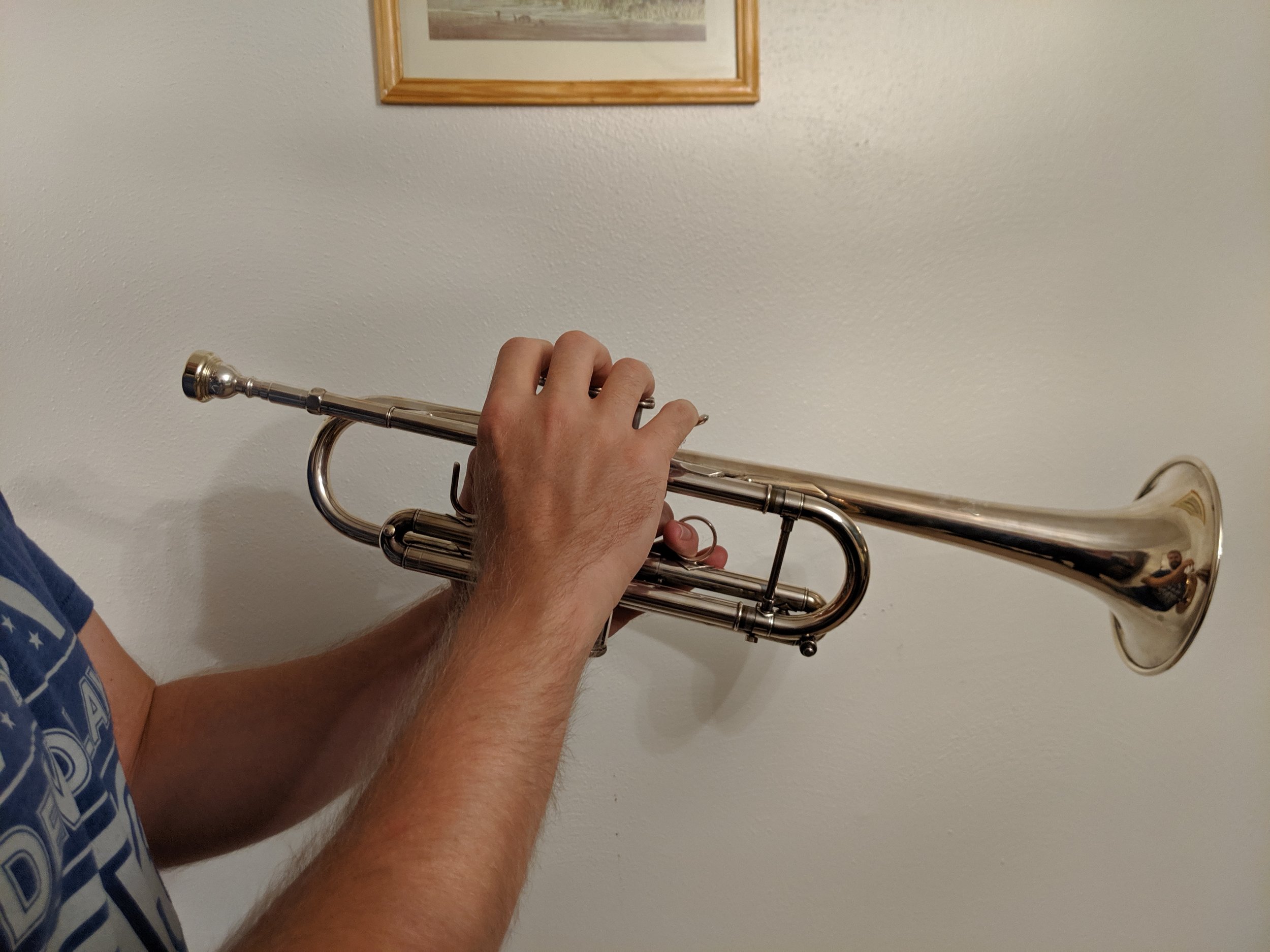

The downside of trumpet valves (aside from the compromise tuning system… WAY too early for that topic, but we’ll get there) is that there are only 7 distinct combinations that create different lengths. Starting from open (everything up, notated on fingering charts as “0”) we move to pressing the second valve (often notated on fingering charts as “2”). This has the shortest extra tubing and lowers the pitch by a half step: the smallest increment in Western music (micro-tones are a thing that may or may not get covered by this author). If we approximate that that additional length gives you that half step, then we need twice that for a whole step. Good news! The tubing on the first valve is just about twice the length of the second. So, pressing down only the first valve (“1” on a fingering chart) will lower the sound a whole step from an open note. Let’s keep going. To go another half step (this interval of 3 half steps is called a minor third) you’ll need to find tubing about 3 times the length of the tubing on the second valve. If you’ve been keeping track, we can accomplish this by pressing down both the first and second valves together (“12” on most fingering charts). But wait! What about the third valve (you guessed it: fingering charts call that one “3”)? Well, the third valve actually is about 3 times the length of the second valve, so technically, pressing the third valve alone will give you almost the same length as pressing the first and second together. Most of the time it will be easier (from both a tuning perspective and that the ring finger is typically weaker than the others) to use the 1 & 2 valve combination rather than 3. That said, it’s important to keep that third valve in mind here as the next half step down (4 half steps now, called a major third) is accomplished by adding the second valve to the third (yep, “23”). Continuing on, we keep the third valve, but change from second to first (just like going from our first half step to the whole step), arriving just shy of what would be a five half step drop (called a perfect fourth). Notice I said “just shy.” Well, remember that side note about the compromise tuning system? Without going too much into it, just remember that the combination of first and third valves (“13”) is a little bit too short. This means the correct fingering is the combination of the first and third valves AND a slight (~quarter inch) extension of the third valve slide (you might remember from “Your First Notes” that I said you’d need that ring… this is why). One last valve combination! This time you get to press down all three (“123”). Now you’re 6 half steps down from that open note (called a tritone). This combination, like “13” is also too short, but even more so than before, requiring a much longer extension of that third valve slide (~one inch). You’ll want to check this against a tuner at some point as each trumpet will be ever-so-slightly different. Don’t worry too much about it now, though. We’ll cover tuning and tuners in-depth another time.

So, those are your seven different valve combinations: 0 (open), 2, 1, 12 (or 3), 23, 13 (with slide), and 123 (with more slide). But wait! If there are only seven combinations, how do we play more than seven notes? That’s where the changing air comes in. Back in the old days (think pre-1800), trumpets didn’t even have valves. These are now called natural trumpets or baroque trumpets, referring respectively to the natural harmonic series or the baroque musical period during which they were played (They actually are still played sometimes, and I have one. I think it’s awesome!) The only way these trumpets could change notes was to take advantage of harmonic frequencies and changing partials (a term brass players use for the different notes along the harmonic series) primarily by increasing or decreasing airspeed. And if they needed to play a note between two notes in the series, they’d have to change out a slide to make the entire trumpet a different key! Valves really simplified that process.

So lets talk about changing partials. The lips are involved, but air is much easier to think about (and control), so we’re going to focus on that first. Generally speaking, the faster air is moving through the trumpet, the faster the sound wave produced can vibrate. This means that faster air should equal higher notes. The flip side of that coin is that slower air will allow for lower notes. So far, we haven’t talked about what note you’re actually playing. That was deliberate. You’ll also notice that though I referenced fingering charts, I didn’t include one. Right now we’re focusing on how to play, not what to play. So, take a breath and play a note. Hold onto it, then try to speed up the air. A good way to do this initially is to think about blowing more air and playing louder. Try this out until you can get the note to change. It may take lots of tries, and that’s perfectly OK. Depending on what note you’re playing, the difficulty of changing notes can vary widely. Despite the notes being closer together as you go up (see the harmonic series above), it gets harder and harder to accurately change. Once you’ve figured out playing a higher note, or if you just want to try something different, try changing to a lower note. This will be a reverse process of playing higher. The air will need to slow down. To begin, try thinking of blowing less air, or playing quieter. Depending on what note you’re playing, you may not be able to go lower on an open note, so don’t be discouraged if it doesn’t happen. You may have to go up before you can go down (and vice versa).

Once you’ve started to get a feel for changing notes with your air, try out those fingerings from up above and see how the patterns work when starting from different open notes. Next time, we’ll look at figuring out specific notes and how to read music. For now, just have fun! Change notes, and try to make up a tune all on your own.